A Migration Era Puzzle from Evebø in Norway

/“This is a striking example of how many strange things may have been put in the graves. But how many things have been lost to the fragility of the material, or the indiscretion of the excavation!”

The purpose of archaeology is the acquisition of knowledge and understanding of the human past by studying studying artifacts and their contexts. Through the accumulation of such data, as well as applied interdisciplinary methods, archaeology has allowed us to decipher languages and make tangible societies that would have been only footsteps in the sands of time, destined for erasure if it weren't for the academic, retroactive battle against our collective forgetfulness. Effectively, this makes archaeology almost a kind gnostic pursuit, if you’ll excuse such an unorthodox use of the term.

Though the modern approach to history, and even the modern human’s conception of time itself, differs from the mythic and legendary perspectives of the vast majority of our ancestors, I believe that ever since the dawn of our sentience, humanity has always been entranced and perplexed, and curious about its origins. It is only recently that the historicist approach, though a long time coming, resulted in the commonplace chronologies and methodologies of today.

I don't think that the two approaches to time are mutually exclusive. Not entirely at least. In terms of making sense of what and who we are, and finding meaning in our origins and development, the antiquarian sciences are indispensable, even if the interpretative hoarding of artifacts and data can only take us to the proverbial so far. Then there is the trite cliché saying, though entirely true, that the more we know, the greater becomes our understanding of how much we don't understand. For those of us dreaming of this "understanding", the study of the past is distinguished by a certain dissatisfaction that fills us with both with both wonder and frustration. Yearning for an "Eternal Return” in spite of our separation, towards a realization that, in the words of the poet Tor Ulven, "you, too, belong in a Stone Age". As we know we can only move forward, if time is a circle we must necessarily return. If so, there would actually be no escape. But I have hedged my bets just in case, on this god forsaken antiquarian vocation, and my obsessions with the past.

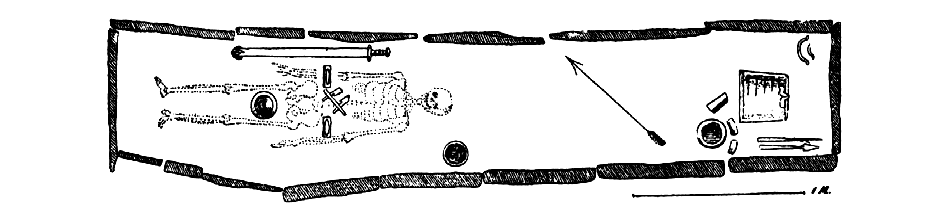

The dimensions and allignment of the "Evebø chieftain's" burial chamber from Gustavson (1890a: 4)

One find that exemplifies, to me, all of the above is the princely burial at Evebø in Gloppen, Norway. It ranks among the finest archaeological sites of all Scandinavian prehistory (though as always, criminally overlooked outside of its niche field). At its excavation in 1889, the barrow was 25 meters across and 2 meters tall. It was built around a long and narrow stone chamber sealed with birch bark, where a man was laid to rest on a bear skin in the final quarter of the 5th century. His body was dressed in the finest garments available to the upper crust of Migration Era Scandinavia. A red tunic with gilt metal clasps, and a rectangular cloak with tassels (a so-called prachtmantel), both of which included richly dyed zoomorphic brocade bands. On his waist was an eye-catcher of a belt covered in bronze fittings and an inlaid fire-striking stone (a popular status symbol of male dignitaries at the time). His trousers were probably tightly tailored. He was buried with a sword with a beautiful but functional wooden hilt, in a scabbard decorated with gilt fittings. A shield covered his lap. Then there was a lance, an angon (a Germanic harpoon-style javelin). In other words, a complete set of weapons suitable for a regional warrior king, no doubt part of an influential dynasty. This must have been quite a time to be alive, with Germanic kleptocrats basking in the Roman collapse, setting the scene for history yet to be made, and blissfully unaware of the climate crisis and Justinian Plague coming right around the corner.

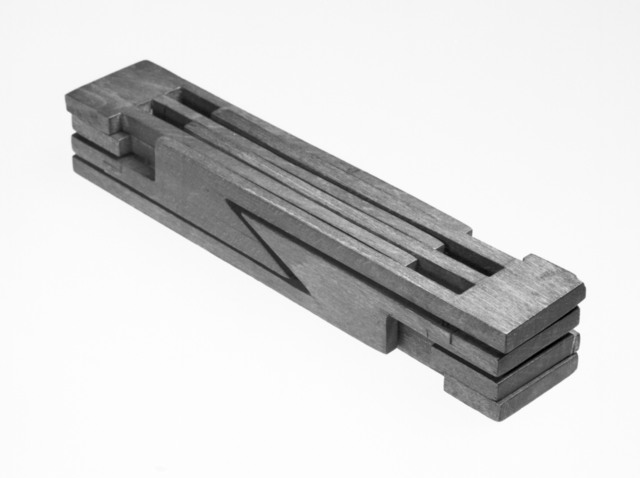

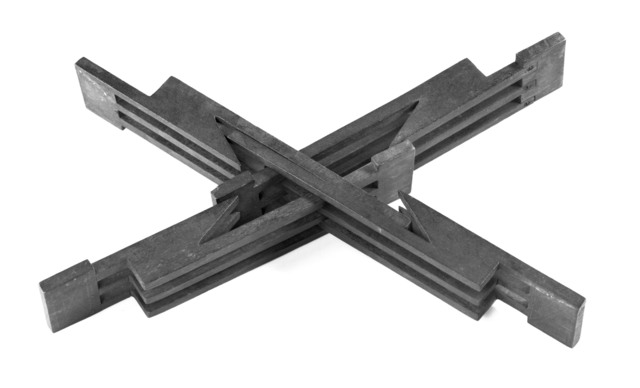

The burial reflects a man who made the most of his networks in an unprectiable time where overseas trade involved rowing across the ocean. A gold solidus minted under emperor Theodosius II converted into a medallion to be worn around the neck, a Roman glass beaker from today's Syria, a wooden feasting bucket plated with copper alloy, pottery, weights and scales, and several other items and trinkets. Among the latter is the focus of our article: A strange wooden object of uncertain significance and purpose, later dubbed "the mind ring". Here are some of the original fragments:

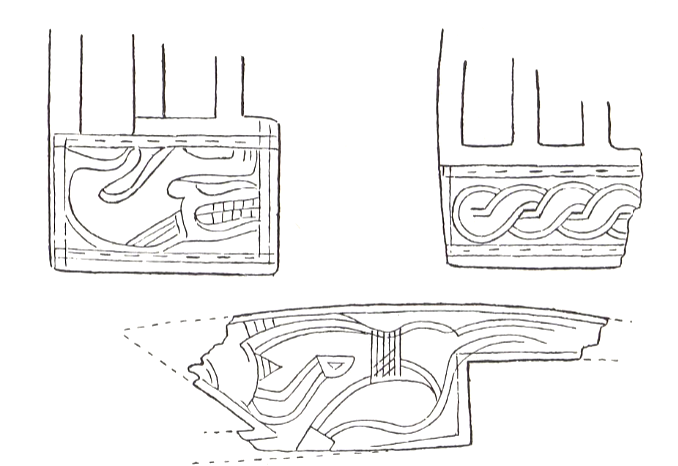

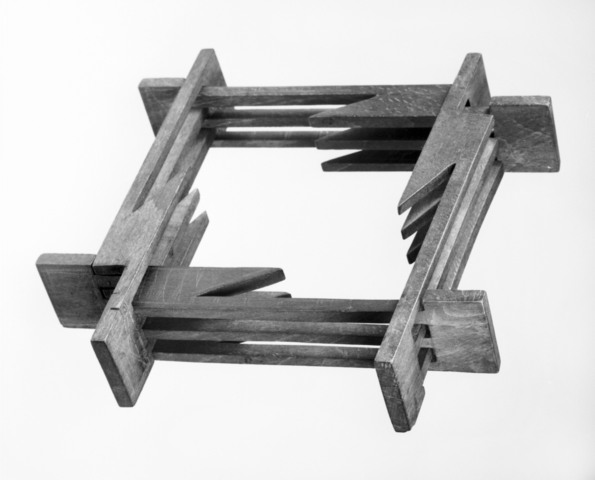

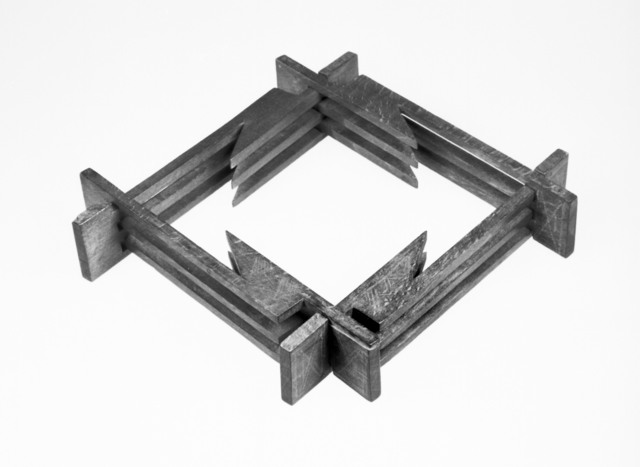

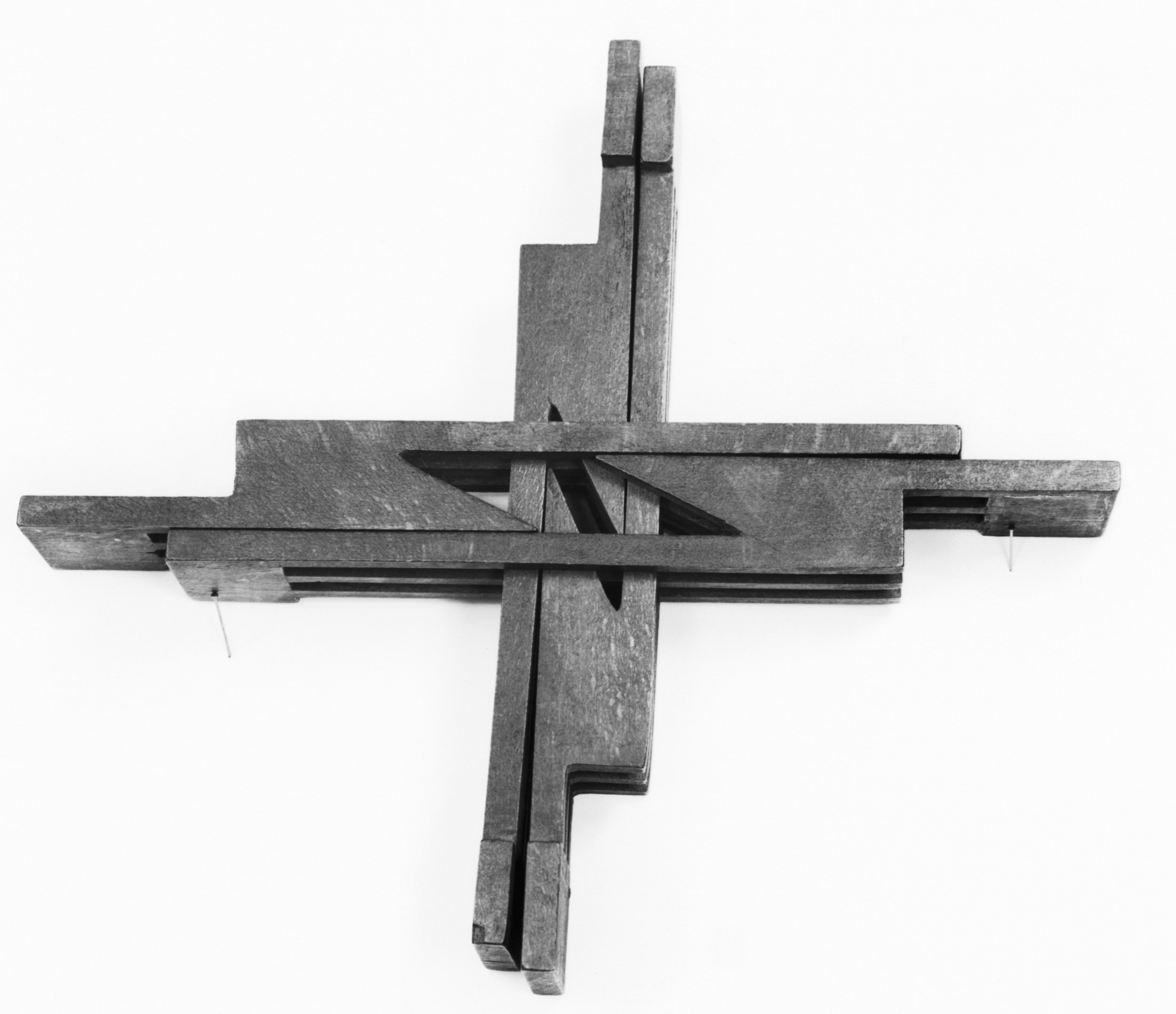

The object lay over the man's waist region, by the belt, and consisted of a warped and broken frame of three barbed, interlocking pieces of wood. A fourth part had apparently rotted away. It became clear that the object, which was approximately 20 centimeters on each side, had formed a square carved from one single piece of wood. On further inspection it was also revealed that this was not fixed: Originally, the object could be shaped and reconfigured into a variety of geometric shapes, and folded into a rectangle, presumably for easy storage. It was decorated with simple incisions of geometric lines and patterns, as well as two Nydam style depictions, one of a beast (perhaps a dog or a wolf) and another figure more difficult to identify.

Sketch of "The mind ring" as it was found. From Gustafson (1890a: 12)

The object appears to be some sort of puzzle, toy, or tool. It was precisely carved from one single piece of wood without resorting glue or joins of any kind. It's obvious that whoever made it was a highly skilled woodcarver with access to very fine tools. The hand that carved its decoration seems less steady, and it might have been secondary addition. Gabriel Gustafson, the head archaeologist who supervised the excavation and stands as the prime scholar associated with the object, uses the technical term monoxylon to describe an item carved from one single piece of wood (Gustafson 1890a: 29).

It's worth mentioning that monoxylic objects were well regarded in later Scandinavian folk art. Associated techniques were often used to make courtship gifts (This blog post by my wife gives a few examples), as they demonstrated the great skill of the carver. As we can imagine, there might also have been an esoteric level to the concept of something that is completely made out of itself without breaking its structure, and to produce something that is entirely integral to, and indelibly linked to itself. We'll be returning to this subject later in the article.

Decorated fragments. From Johansen (1979).

The term "mind ring" (tankering) is foremost associated with the Gabriel Gustafson, as he wrote the bulk of the material dealing with the object. However, he attributes the coining of the name to Johan Sverdrup who felt reminded of popular wooden puzzle games. Gustafson makes it very clear that he did not quite agree with Sverdrup on the matter (hence he usually refers to the (so-called) "mind ring", or "the ring-puzzle" in quotation marks), because Nordic puzzles generally consist of several loose pieces. He could find no parallels to the object within Scandinavia beyond speculation, in the form of a few peculiar wood fragments reported from since disturbed burial contexts. Eventually he found a nearly identical artifact, apparently of Persian origin in London's South Kensington Museum (today Victoria and Albert Museum).

The "persian puzzle" of South Kensington Museum. From gustafson (1890b: 8).

The similarity between these two artifacts lead Gustafson to pursue the idea that the Evebø object came from the orient. There are two issues with this: First of all the "Persian puzzle" was apparently produced in relative modernity, and as it turned out, the Evebø "mind ring" was carved from locally sourced birch, excluding the possibility of import. With the undeniable likeness between the Persian and Norwegian objects, many later scholars have postulated that the Evebø object was based on eastern counterparts (cf. Hatling 2009: 69), though no such ancient artifacts have come to light, as far as I know.

With more than a millennium and half a world separating the two, Gustafson failed to find any monoxylic counterparts in the orient, apart form certain Islamic Quran desks, and western Chinese pedestals and religious effigies with moving limbs produced with the same technique. He found it striking that many such monoxylons were intended for sacred or ceremonial use, which gave him confidence that that the "puzzle toy" from Evebø in fact had religious importance. If so, the underpinning concept might be expressed in symbols seen elsewhere in Scandinavian Iron Age ornaments. Perhaps, he argued, the object itself could be folded into a shape reminiscent of certain symbols in Migration Era art.

Let's pause for a semiotic meditation on the so-called thought ring. Being carved from a single piece of wood, the four parts that comprise the object are seamlessly and completely anchored to one another, or to itself. Are we to regard its constituents as separate, or same? The “limbs” mirror one another in perfect symmetry. Each share the same origin in the thing itself. No external material was added to produce the object. Though created, it was never built or assembled (though we might say the physical object was sculpted). You cannot take it apart without breaking it. It is self-contained. Complete, yet bound. Further, we may discern that the object appears to have an active aspect, and an inactive, passive, aspect. Active when manipulated or shaped into any desired form the object allows, and passive when folded, or closed to be put away and stored. We can note that the object was found in close proximity to the belt, an important attibute of his identity, power and status. It was laid on the deceased persons torso in an open - square - configuration in conjunction with the burial ceremony, which suggests an intimate relationship between the dead and the object. We may presume that this was an important public event with many witnesses. There is nothing random about the selection and placement of objects. They are statements, but what is being said, and what story were they trying to convey through these objects? Was it a treasured curiosity? A final gift from a loved one? Was it used in lithurgy? Did it work as some kind of divination tool? Was it used to illustrate principles of religious, philosophical or cultural importance? Or was it simply the fancy toy of a priviledged child?

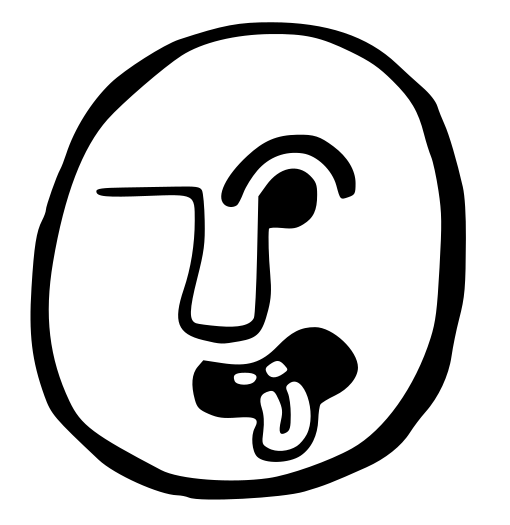

To return to Gustafson, we can't expect to find the Evebø object depicted, but there are some symbols in Iron Age art that remind us of its various configurations. When fully opened there is a certain likeness to the "looped square" that came to popularity in the Migration Era, and is sometimes called a “valknute” in later Norwegian folk art (not to be mistaken for that other “valknut” symbol, which is a modern anachronism). Gustafson notes that the loops in the corners are sometimes minimally small, highlighting its square shape (1890b: 20). The roughly contemporary bracteate from Lyngby, Denmark is particularly interesting, as the symbol is enclosed by a ouroboros, which is a snake swallowing itself, and a symbol of unity and eternity through its own consumption and self-reproduction. Could the Evebø-object have conveyed a similar symbolism, of a totality is nothing without its own uncompromised self? In Norse mythology this idea is expressed in the Midgard Serpent: On the one hand a horrific monster and object of dread, but also a cosmic sustainer without which the physical world cannot continue to exist. It is both antagonist and counterpart to the god Þórr, a divine protector, who is also a wrathful deity constantly hovering on the verge of cosmic annihilation due to his ongoing conflict with the aforementioned serpent (Storesund 2013: 73), and they seem locked in a world-affirming, cosmic compromise or paradox.

Gold Bracteate from Lyngby

It is also clear that Scandinavian society later developed an affinity with the symbolism of knots. This is typified in the Viking Era Borre style of art, with its elaborate knotwork, and the gaze of gripping beasts. Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson hypothesizes that Borre style ornaments were ascribed apotropaic properties, and brings attention to the fact that Norse craftsmen seem to have avoided Borre style ornaments on offensive weapons (sword hilts, for example). On shields they would only be visible to the carrier (Hedenstierna-Johnson 2006: 321). Likewise, the the Lyngby amulet had the looped square on the adverse side, facing the wearer's body. Gustafson also compares the puzzle's cruciform to variants of a design known from occasional Iron Age and Early Medieval objects that appear to "represent two plates, which by means of a longitudinal groove in the middle are stuck into each other. If that is to be done in reality the whole must be wrought out of one single block" (Gustafson 1890b: 21). Though his main example is first and foremost found on early Christian runestones in Sweden, we may take note of the argument that a cross is not always the cross as far as Iron Age Scandinavia is concerned.

Gustafson's semotic toolchest (Gustafson 1890b: 17)

While we are likely unable to extract the intent, function or symbolism behind the Evebø object in any way that would finally satisfy our curiosity, it stands as a preciously unique contribution to our understanding of Iron Age culture and society. And while the range of information related to ancient Scandinavia accumulates, there is some safety in knowing that there is also wonder and mystery to be found even between the growing heaps of data for generations to come.

…

Enjoying the content? Support Brute Norse on Patreon.

See more pictures of the Evebø find via Bergen University Museum on UNIMUS.

Gustafson, Gabriel (1890a): Evebøfundet og nogle andre ny gravfund fra Gloppen. Bergens Museums Aarsberetning for 1889. John Griegs Bogtrykkeri: Bergen

Gustafson, Gabriel (1890b): A strange wooden object found in a Norwegain tumulus. Bergens Museums Aarsberetning for 1889. John Griegs Bogtrykkeri: Bergen

Hatling, Stian Hindar (2009). Gloppen i folkevandringstiden - En sosial analyse av evebøhøvdingen. Masteroppgave i Arkeologi. Institutt for AHKR: Universitetet i Bergen

Hedenstierna-Jonson, Charlotte (2006). Borre style metalwork in the material culture of the Birka warriors. Fornvännen 101. Stockholms Universitet

Johansen, Arne B. (1979). Nordisk dyrestil - bakgrunn og opphav. AmS skrifter 3. Arkeologisk Museum i Stavanger.