Certain expectations follow the Fulgur catalog. As the common ground of art and magic forms their main scope of interest, Fulgur's books and journals seem to burst with pictures, poetry, and colorful illustrations. In the case of their often oversized volumes, they are a far cry from the ubiquitous pocket format fodder found in the new age section of your local bookstore, and truly worthy of rare hours of retreat and contemplation. Their artsy and bookish alibi recalls the old times when it was self-evident that art, magic, and academia were parts of the same trinity.

A Book of Staves does not diverge from this esoteric art book tradition. Nicely bound in its coffee table format, a debossed visual palindrome in the form of a charm hides beneath the dust jacket. With its 120 pages it is not a dense book by any means. The word count is front heavy: The book begins with a statement from the artist, superseded by an introductory essay by the British archaeologist and art historian Robert J. Wallis. Both supplied with a parallel Icelandic translation. From there on, most of the text consists of titles and quotes from the Hávamál in Old Norse besides Carolyne Larrington's popular English translation. This is intended to complement the artwork.

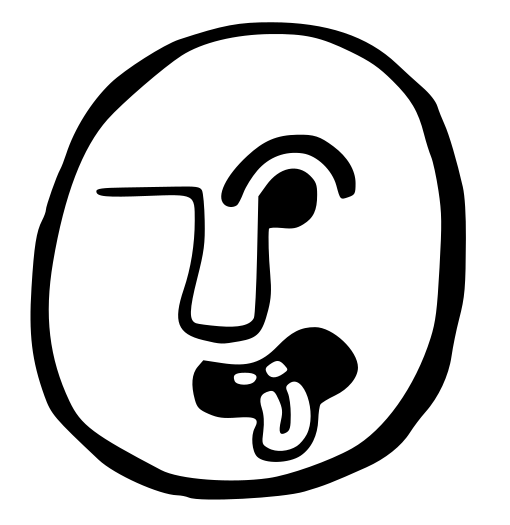

As for the artwork itself, it would be more fitting to refer to the individual images – like the artist does – as spells. For all intents and purposes, A Book of Staves is not a typical "art book", but a neatly curated series of visual charms: It contains 39 individual galdrastafir, 18 of which are based on the equal number of magical charms reckoned by Odin in the ljóðatal section of the eddic poem Hávamál (stanzas 146 through 163). Then, under his “Moon Rituals” follows nine astrological staves, then eight non-sequential “Small Staves” on various magical themes, and finally four staves for the elements.

I was immediately surprised at how well the “songs” of ljóðatal worked with Bransford's visual re-imaginings. In hindsight, Odin's secretive charms sound exactly like the sort of things you'll find in many books of magic, whether in continental grimoires, or the Scandinavian “black books” and Icelandic staves the early modern era. His “Small Staves” come across as faithful developments of this tradition as well. Yet his is no sterile contribution. The artist's playful signature, whether by his use of watercolor, or the sketchwork revealing the underlying geometry of the charms, removes the usual anonymity of his source material. Though unsaid, Icelandic staves work excellently as abstract art.