Clubbing Solomon’s Seal: The Occult Roots of the Ægishjálmur

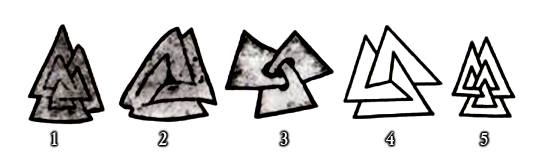

/No subject is too sacred to be spared from the Brute Norse fatwa against disinformation. Vets to the blog may recall my rough-handed, but no doubt justified assault against the so-called *valknútr and the anachronisms surrounding it. Now, time is long overdue to raise the banner once more and declare hunting season on yet another sacred calf of the misguided and opportunistic: The ægishjálmur.

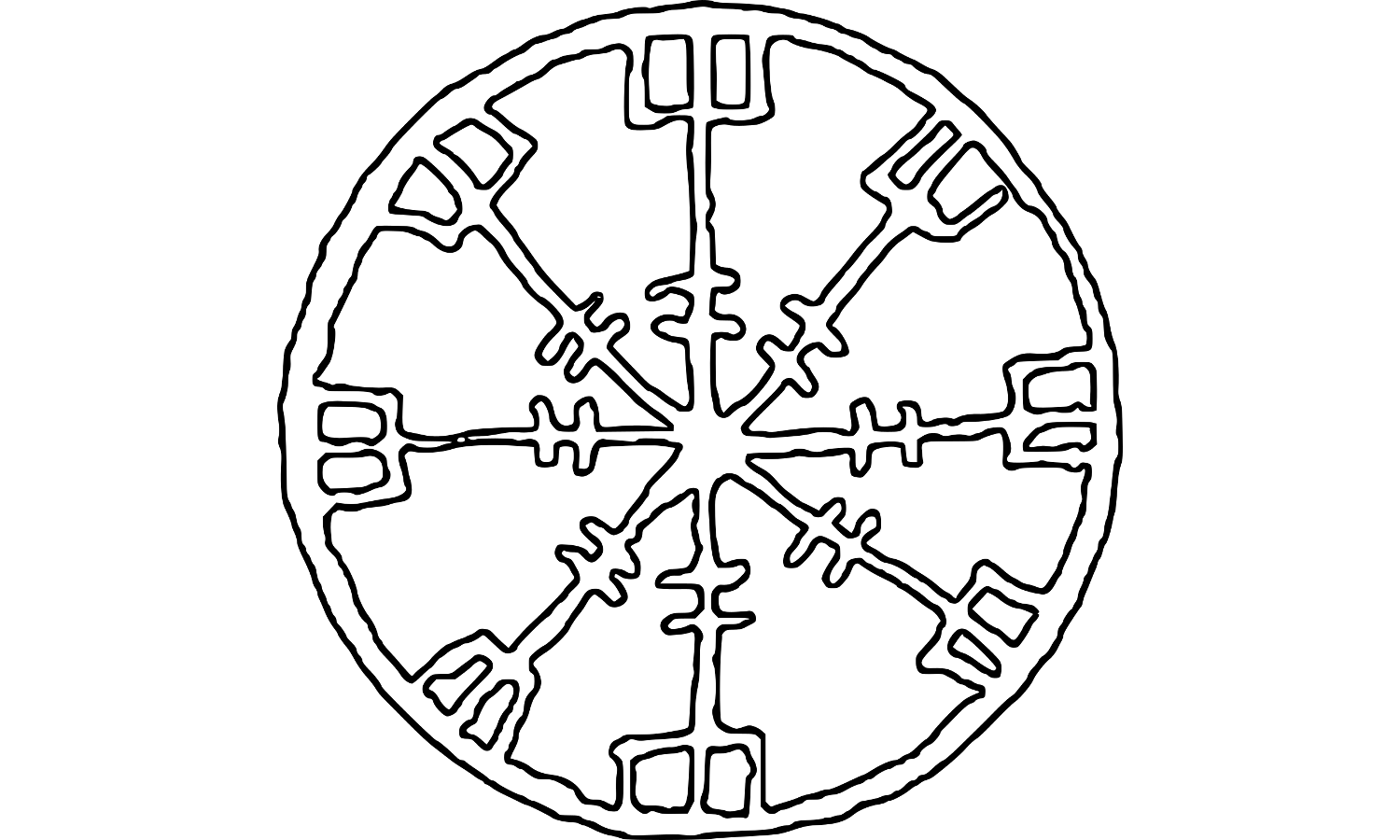

The ægishjálmur is certainly one of the most recognizable symbols from the corpus of Early Modern Icelandic magic, collectively refered to as “galdrastafir”, or “magical staves”. Though often spoken of as a charm to daze or instil fear in enemies, the stave’s exact purpose varies from manuscript to manuscript. In some cases it helps you get laid, in others it makes your angry boss chill out. The symbol itself takes a variety of forms, though usually depicted as a cruciform or radial sign with either four or eight spokes and fork-like protrusions that bear a passing resemblance to runes.

For the convenience of more impatient readers readers I’ll summarize my point right now: The ægishjálmur is not a Viking Age symbol under any reasonable definition, but a post-Medieval magical appropriation of an older concept, which I’ll be referring to by its Old Norse name. The tradition comes in two main forms:

1. A magical helmet called ægishjalmr, mentioned in Old Norse legendary literature.

2. A symbol by the name of ægishjálmur, depicted in Icelandic occult literature from the Early Modern Era.

For clarity, the first will be referred to in italics by its Old Norse form ægishjalmr, while I will reserve the modern Icelandic form ægishjálmur for the symbol. The two are different and distinct, but not totally unrelated.

What ties them together is a retrospective antiquarianism by authors of Icelandic magical texts, popularly referred to as “galdrabækur” (sg. galdrabók). These fellows must often have been antiquarians and book collectors, and as Icelanders they had a unique access Old Norse literature through widely circulated paper manuscripts, as well as continental occult literature pertaining to what is more commonly called “ceremonial magic”. The result was a distinctly accultured vernacular magical tradition, retaining elements of practical folk magic, kabbalah, Christian mysticism, demonology, and Norse fakelore. Though this is essentially the work of well-read and learned men, Icelandic magic is often portrayed as the magic of shit-kicking peasants with limited means, which makes the galdrabók-tradition seem more ancient, isolated, and local than it truly is.

Good Riddance to Viking bogus

If my intent was to simply debunk the ægishjálmur as a Viking Era symbol, this article would have been significantly shorter. However, the history of the ægishjálmur is a rather interesting and often unspoken one, so consider this a sort of lecture in the strange saga of Nordic magic. While I have singled out the ægishjálmur for this study, it’s important to understand that the same critique applies to all the galdrastafir more generally, especially other radial symbols like the Vegvísir. This article is deemed necessary due to the extreme influx of ægishjálmur nonsense polluting portrayals of Norse culture either by reenactors, or in popular culture. Secondly there are many misconceptions about the symbol in esoteric and Neopagan communities as well, and hopefully this will serve to clear a lot of it up. For the sake of historical accuracy, the galdrastafir should not be permitted in any Viking Era context. If you see a reenactor sporting one at an event, make them eat it, whatever the material is.

No graffiti, no artifacts, no depictions in textiles or metal, absolutely nada, nothing even remotely similar to the symbol has ever been attested in Norse art. None the less, the ægishjálmur is persistently tied to Viking Age spirituality and aesthetics in an impressive range of anachronistic combinations. It only takes a quick google search reveal the extent of this conspiracy of ignorance, with a tide of ghastly crimes of fashion and historical falsehoods, perpetrated by craftsmen, designers, and sellers across the Western Hemisphere, who are either oblivious or willfully lying about the actual historical context of the symbol.

As a top design choice for peddlers of souvenirs and other cheap horseshit, there are painted shields, leather goods, graphic tees, jewelry, weapons, wristwatches, duvet covers, flip flops, passport covers, and all that jazz. Not always claiming historical authenticity of course, but always marketed as a “Viking symbol”. Another popular claim holds that it is a bind rune, and so it is popularly depicted inside a circle of Elder Futhark runes that predate any known depictions of the ægishjálmur by damn near a thousand years. This insult to runology is self-evidently bogus.

If you see somebody with this passport, make sure they find their way home. Source: Allpassportcover.net

Let’s hear it for the primary sources

So we’ve established that there is an object in Old Norse literature called ægishjalmr, as I’m sure you knew already. The eddic poems Regins- and Fáfnismál are probably the most cited sources for the term, but it is actually mentioned in a few different norse texts. The first compound ægis- is conventionally translated as “of terror, horror, awe” while -hjalmr simply means “helmet”, and I’ll be accepting this reading for the remainder of the text.

As the author of The Galdrabók: An Icelandic Grimiore (1989), the esoteric scholar Stephen Flowers was probably among the prime movers in terms of bringing the ægishjálmur to international attention, at least in the counter-culture. This is a commendable early bird effort even though I don’t share all of his convictions. Particularly that hjalmr should be read as “covering”, because this was the original meaning of the word etymologically. I don’t find this reading acceptable for the Old Norse material at hand, and have some general disagreements with his interpretations (cf. Flowers 1989: 122; 1987: 48. In an earlier draft of this article I was overly dismissive of some passages in Flowers’ books, and I realize in retrospect that this was based on a faulty reading. It also detracted the main message of the article, and therefore I have cut those pieces out of the current version).

My point is that there is hardly any leverage to support the claim that this “helm of awe”, or however one would prefer to translate it, is to be understood as anything but a helmet in the original sources. In Fáfnismál, the dwarf-turned-dragon Fáfnir merely states he “wore the terror-helmet” to keep people away from his treasure. There is never any reason to resort to an exotic reading, unless we assume that 13th century audiences were familiar with obscure occult discourse from the times between the birth of Johan Sebastian Bach and the death of Friedrich Nietzsche. It is never suggested to be a sigil, a drawn figure, or anything more abstract than a piece of magical armor worn by a fantastic creature. And why not? Dwarves are renowned smiths, not graphic designers.

In the prose interlude between stanzas 14-15 of Reginsmál we are none the wiser: “Fáfnir lay on Gnita-Heath in the shape of a worm. He owned the terror-helmet, which all living things are afraid of” ([…] Hann átti ægishjalm, er öll kvikendi hræðast við). In Vǫlsunga saga, the helmet in question is referred to both as ægishjalmr, “a helmet”, and “Fáfnir’s helmet” (hjálm Fáfnis). Significantly, when Snorri Sturlusson gave his prose version of the myth in Skáldskaparmál he remarks that “Fáfnir had then taken that helmet that Hreiðmarr had owned, which is called Ægishjalmr, and put it on his head, which all living beings are afraid of” (Fáfnir hafði þá tekit hjálm, er Hreiðmarr hafði átt, ok setti á hǫfuð sér, er kallaðr var ægishjalmr, er ǫll kvikendi hræðast). If there was any tradition of a magical symbol called ægishjalmr in Snorri’s time, he clearly didn’t get the memo. He’s certainly not too shy to make similar connections in other cases.

In the 14th century s̶c̶h̶l̶o̶c̶k̶f̶e̶s̶t̶ knightly romance Konráðs saga keisarasonar (or, "The Saga of Konrad Emperorson” if you insist), the motif of a helmet-wearing wyrm is recycled in an odd heroic pastiche, where it also appears to be a literal helmet perched on the beast’s head.

The Gök Stone, Sö327

But there is also a second, proverbial use of the term ægishjalmr, which appears in the context of strong political and military leaders who are able to easily conquer and crush opposition. In this context the idiomatic phrase “to carry/wear the helm of terror before (someone)” (bera ægishjalm yfir) means “to subdue”. In Laxdæla Saga (ch.33) it occurs when one of the main characters, Guðrún Ósvífrsdóttir, recalls a dream in which she wears a gold helmet with inlaid gemstones that is too heavy for her. She is told the helmet symbolizes a fourth future husband who will prove domineering and curb her manipulative ways. Even in the Biblical translation Stjórn we encounter bera ægishjalmr as a metaphor for a zealous and oppressive personality. This kind of phrasing is fairly common in Old Norse, cf. sitja á friðstóli which literally means “to sit in the peace-chair” but is really a proverbial way of saying “not causing a ruckus”.

Right before that start of the 15th century, the motif of the ægishjalmr appears to have developed into an even more abstract concept. Sǫrla þáttr, a legendary tale accounting for Flateyjarbók’s depiction of the perpetual battle called Hjaðningavíg, the medieval author(s) refer to the character of Hǫgni as having “helm of terror in the eyes” (hafa ægishjalm í augom). The idiomatic phrase hafa ægishjalm í augum when referring to the warrior’s piercing and dangerous gaze fits right in with Icelandic literary convention, but more importantly it bridges two similar motifs in Norse legendary literature: One is the the magical, fear-inducing artifact adorning the powerful monster or warrior. The other is the paralyzing, disarming, or otherwise weaponized gaze possessed by particularly powerful saga heroes and mythological figures. This attraction of motifs may have set the course for later developments of the ægishjálmur in Icelandic magic.

Iceland’s occult revival

Quick recap: The ægishjalmr first appeared on the map as a legendary magical artifact, then it gradually developed as a metaphor for particularly domineering and aggressive personal traits in the High and Late Middle Ages. But it is not until about 1500 that we first see the word in contexts detached from its original meaning, and it begins to appear in the Icelandic magical vocabulary. The very oldest Icelandic book of magic comes down to us as the Icelandic Leech-Book, or Lækningakver preserved in the manuscript AM 434 a 12mo. This is essentially medical manual with significant magical elements.

By now, Nordic magic had been under the spell of Christian mysticism and continental magic for several centuries. Among the hundreds of runic inscriptions acquired from medieval Scandinavia, a number of them display knowledge of charms we might sooner associate with the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn than Norse culture. We find versions of the magical phrases AGLA, Abracadabra, and several Sator-squares all written in runes. There may be many reasons for why runes were preferred in this context. Most obvious was the lack of Latin literacy in the wider populace, and so runes were a necessary technology to resort to when communicating written magic intended to be read aloud. Rune sticks with Latin language prayers were essentially “prayer apparatuses” for the uneducated, all of that stuff is pretty quotidian in Medieval Scandinavia (It’s often overlooked that the vast majority of runic inscriptions are post-Viking Era). However, the Christian era also brought an increased mystification of the runes that only increased when it came into contact with other magical traditions (Davies 2009: 31), and as the runes faded into obscurity as the writing system of the common folk, we might expect that they rose to magical prominence.

Bottom of a 14th century coopered vessel with sator-inscription. Örebro, Sweden (Nä Fv1979;234)

The only mention of ægishjalmr in Lækningakvær comes from a washing spell intended to rid the spellcaster of hatred, wrath and persecution: “[…]May God and good men look at me with mild eyes, the ægishjalmr I carry between my brows […]”. The full spell, which includes saying the lord’s prayer three times, makes no references to the pre-Christian world save for the term ægishjalmr. The same can be said for the vast majority of the later galdrastafir as well, but this particular spell does not instruct us to draw any symbols.

However, the manuscript features a couple of early examples of galdrastafir, including what look like a primitive cruciform variant of the ægishjálmur in a spell intended to stem a chieftain’s anger. It is but one of several spells in the book displaying knowledge of continental magic, and demands that the magician draws the symbol (interestingly, it is referred to as a “cross”) on his forehead using yarrow drenched in their own blood. Then he should go before his master and invoke a series of names and phrases such as AGLA (One of the “secret names of God”, and a magical acronym corresponding to the phrase Atah Gibor Le-olam Adonai, "You, O Lord, are mighty forever”). It also invokes the angelic order of the ophanim, drawn directly from Judaeo-Christian mysticism and Kabbalah. Many contemporary magical practitioners will no doubt recognize the term, for example in the Lesser Banishing Ritual of the Pentagram. The two must obviously not be conflated, but their common historical influence shows.

Early magical stave from Lækningakver (AM 434 a 12mo). Last quarter of the 15th century.

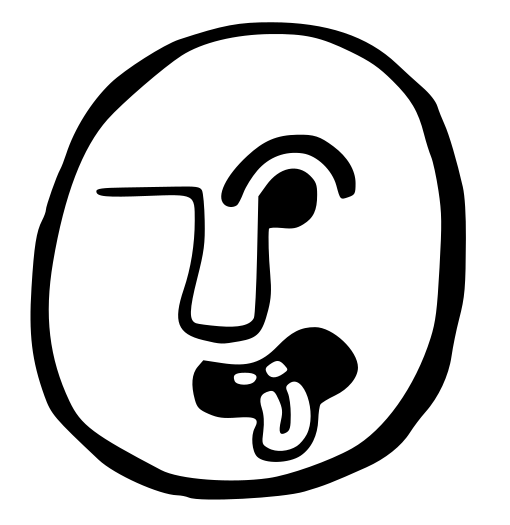

It’s no coincidence. The striking diversity of galdrastafir in the galdrabækur owes less to local traditions and more to scholarly occult treatises of Latin and Greek origin that often claim to have Hebrew sources, and are demonstrably older than any of the surviving Icelandic material. Between the 13th and 15th centuries, magic associated with the biblical king Solomon began circulating around Europe, and from the 1400’s onward we find full-fledged pseudoepigraphical grimoires attributed to his name. That may sound very lofty, but the purpose of their spells are often the achievement of mundane everyday desires such as punishing enemies, identifying thieves, winning lovers, and so on (Davies 2009: 15). The same was the case for mainland Scandinavian “black books”, as well as the Icelandic galdrabækur. This is because continental grimoires were a direct influence on both of them. Sigils are rather absent in much of the Scandinavian material, but got significant traction on Iceland. As I already mentioned, what the ægishjálmur looks like varies from one manuscript to the next, and there are many sigils that grant the exact same magical results, but are variously described with names such as “The Seal of Solomon”. Overall, the vast majority of ægishjálmur-like symbols in the Icelandic corpus are not referred to by that name at all.

A collection of ægishjálmar in Lbs 2413 8vo, 31v. Iceland, ca. 1800.

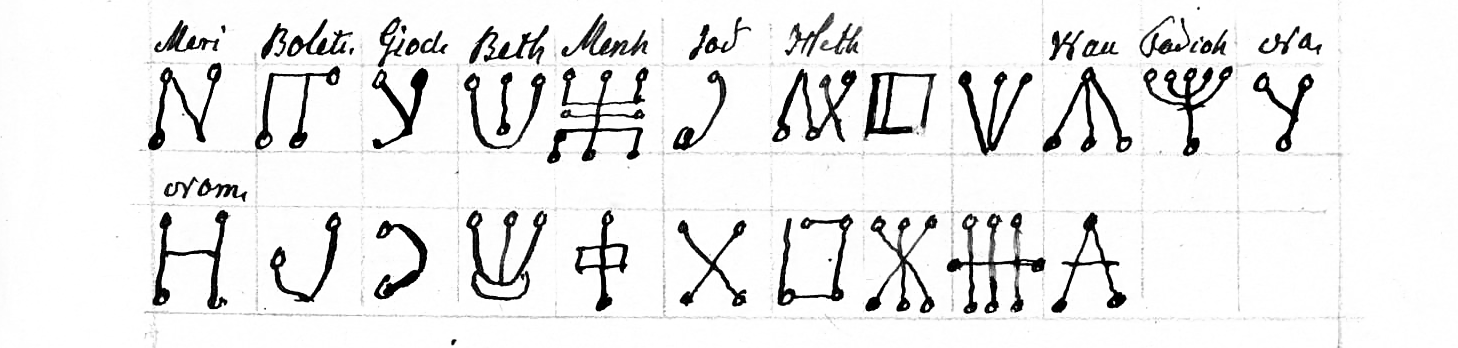

Interestingly, there are several examples in some of the original Solomonic grimoires that are more or less identical to these later Icelandic staves. Have a look at some of the following seals from this 15th century Greek manuscript of the The Magical Treatise of Solomon (Harley MS. 5596), and tell me with a straight face they don’t remind us of Icelandic galdrastafir.

This is quite frankly because the typological origin of the Icelandic galdrastafir lie in Solomonic magic more than anything else, and the occurrence of galdrastafir seems to grow exponentially with the popularity of such traditions in Europe. Many of the more famous forms of the ægishjálmur or other galdrastafir aren’t attested on Iceland until the late 18th century, and often later, peaking around the Victorian Era. Admittedly, a lot of earlier manuscripts must be lost. Mentions of magical manuscripts much predate most of the surviving material, but their development from absent or primitive sigils to more complicated ones must also be considered in this equation.

I started this article with a wee trap. I’m sure many saw the top picture and immediately thought it was an ægishjálmur, but it isn’t. It’s a sigil cooked up by some anonymous wizard in 15th century Byzantium, who was appealing to the allure of Hebrew mysticism. Among the great tropes of the Western Esoteric Tradition are the attempts at creating ties to respected ancient mystical traditions. Ordo Templi Orientis was founded in the 19th century, but associates with the mythology of the Holy Grail. The Golden Dawn and other Hermetic groups allege a tradition going back to Egypt, and of course there have been numerous obscure Neopagan philosophies that allege a secret doctrine handed down to them since pre-Christian times. This is just part of the jargon of Esotericism.

Likewise, Iceland has always been very conscious of its own history for obvious reasons. Among them the fact that it remembered its own settlement, and was a comparatively literate culture. Nordic countries in general have sought to compare themselves with the larger continental cultures since at least the Christianization. It’s not surprising that this would resonate with Icelandic esotericists, who had the motives and means to make Iceland measure up to the mysteries ascribed to the Greeks, Egyptians, and Hebrews. It is easy to compare the attempts made by Snorri Sturlusson et al. to tie the origin of Norse culture to the fall of Troy, thereby writing Iceland into the same honorable narrative as the Romans. These are hardly even that far-fetched as far as the esoteric North goes: The Renaissance spawned a variety of philosophies such as Gothicism, alleging that Scandinavia was nothing less than the cradle of civilization, and placed Old Scandinavian language in the mouth of God himself.

Anyway, the following stave comes from a the early 19th century manuscript JS 375 8vo. First it identifies the sigil as “The Greater Ægishjálmur” (it provides several different examples of them in other parts) before it goes on to say: “This is the seal of Moses”. A double whammy!

“Þetta er ægirs hiálm n stóre [...] Þetta er Móises innsigle” JS 375 8vo, 46v

While we’re at it, have a gander at the seals of Solomon and David from Huld (ÍB 383 4to), a very beautiful Icelandic manuscript from around 1860. Note the addition of runes in the latter.

Um Rúnir

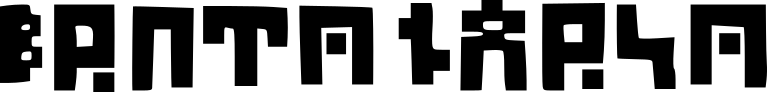

The galdrabækur get really psychedelic when it comes to the subject of runes, and some contain vast compilations of runic alphabets. As you know by now, collecting old books was seen a prestigious hobby among wealthier Icelandic peasants from the Middle Ages onward, and some of these certainly contained antiquarian errata of the runic kind. This must have helped keeping knowledge about them somewhat alive. Iceland, being mostly populated by starving fishermen and nerds, was fertile ground for keeping some knowledge of the runes alive. With some exceptions, this was certainly not the case for the rest of the Nordic area, where runes only survived in a few isolated pockets, or were revived by scholarly weirdos - usually with impressive libraries and noble titles. However, a lot of the runic material in the later galdrabækur appears to be sourced straight from the work of the Danish antiquarian Olaus Wormius (1588-1654), who was very much a pioneer in the study of runes. Some alphabets might have been cooked up by the authors themselves, and yet a few others aren’t runic alphabets at all. Galdrabækur with runes are fine examples of just how willing their authors were to mix and match magical traditions.

Even more fascinating is the inclusion of foreign magical alphabets in these compilations of “runic letters”. They often include Hebrew or Greek, and even fraktur. But these are far from the strangest examples. Several galdrabækur reproduce the magical scripts invented by prominent Western Occultists! I was able to identify the Theban, Malachim, and Crossing the River scripts from Agrippas De Occulta Philosophia (1531), as well as Theophrastus Bombastus’ Alphabet of the Magi, sometimes referred to as “Chaldean runes” in the Icelandic books. Some manuscripts contain certain “Adalrúnir”, which might be a cameo of Johannes Bureus through his runic system “Adalruna”. Bureus was a mystic tied to the 17th century Swedish court, who was greatly inspired by the Enochian probject of John Dee (Karlsson 2009: 195), the court astronomer of queen Elizabeth I. Bureus had some rather trippy ideas about Norse mythology, which he reconciled with his Hermetic and Kabbalistic philosophy through an idiosyncratic reading of the younger futhark. The main issue here is that the “adalrúnir” of Icelandic magic do not resemble Bureus’ runes at all, so I will refrain from commenting further on any influence he may or may not have had on Icelandic tradition.

Parts of Agrippa’s Theban Script. Iceland, Late 19th century. Lbs 2294 4to, 195r

Malachim Script, same manuscript.

“adalrunir” from the Huld Manuscript. ÍB 383 4to, 10v

There’s no shortage of imaginative theories stating that the galdrastafir are in fact elaborate “bind runes”. There is, to put it short, no evidence to support this though the galdrabækir are full of runes and runic cryptography. However, one could make the case that runes were on the interpretational horizon of Icelandic audiences, though in a rather corrupt form (Flowers 1989: 45). I’ll let Christopher Alan Smith, author of Icelandic Magic: Aims, tools and techniques of the Icelandic sorcerers, have the final word regarding the question of galdrastafir as runic:

Working from the a priori assumption that the Icelandic magical staves must be complex binds [...] in a process similar to the ‘sigilization’ developed by modern Chaos magicians, [authors] then twist and bend the facts to suit the theory. The results, predictably, are unconvincing. Even a brief scan of the most extensive grimoire that is available as a translated and published work, Lbs 2413 8vo, shows that there is too much variation for this to be the case. Often, very different staves are prescribed in separate spells for exactly the same purpose. Sometimes, identical staves are used for very different purposes. In short, there is no consistency of the kind one would expect to emerge if an underlying system based on the Futhark runes existed.

Die in battle, go to Valhalla

A Norse-Satanic Axis of Evil

I should probably say something about one of the greatest misconceptions about Icelandic magic, which is that it is somehow Pagan in content. It is not, at least not in any true pre-Christian sense. There is little talk about Odin and the other Norse deities, and a whole lot of talk about Jesus. Undoubtedly, there were periods in Icelandic history where the galdrabækur were highly illegal, being deeply heretical from a mainstream theological point of view. That doesn’t take away from the fact this is Christian magic through and through, and that many books might have been owned by clergy - as the case often was in Scandinavia.

The spells all assume a Christian magical universe in the classic grimoire tradition, where devils can be haggled with or forced to do your bidding, you can invoke power and grace of the angels, and manipulate the world through the emanations of God. It is a form of Christian hacking more than anything else.

If and when the charms mention Norse gods at all, which is rare, they are usually treated as they would in demonology, punching the point across that the old gods are simply devils in Icelandic folk costume (Macleod & Mees 2006: 32). That was the Christian explanation for why anyone would worship idols in the first place, and the church didn’t necessarily deny their existence flat-out. If it weren’t for such demons and other syntax errors of human spirituality, there would be no alternative to salvation. People were lured away from God after he zapped the Tower of Babel. And so there is no reason why the Norse gods shouldn’t be included among the dukes and devils of Hell in Icelandic magic, as this had been the attitude of Icelanders for hundreds of years. The galdrabækur are only taking the Christian critique of Paganism to its logical conclusion. It’s nicely illustrated in the a charm “to make women silent” from ATA, Ämb 2, F 16:26, ca. 1600:

Til þessa hjálpi mér allir guðir, Þór, Óðinn, Frigg, Freyja, Satan, Belsebupp og allir þeir og þær sem Valhöll byggja. Í þínu megtugasta nafni, Óðinn!

Translation:

To this end help me all gods, Thor, Odin, Frigg, Freyja, Satan, Beelzebub, and all of them and those that dwell in Valhalla. In your mightiest name, Odin!

I for one find that rather interesting.

So to all the sorcerers out there with ægishjálmur tattoos:

HAIL THE ÆSIR! HAIL SATAN!

A lot of work went into writing this article. If you enjoyed it please pass it on, and do consider supporting my work on Patreon, or by buying some berserker-themed socks, or something.

Cited publications:

Agrippa, Heinrich Cornelius. 1533. De Occulta Philosophia Libri Tres.

Alan Smith, Christopher. 2015. Icelandic Magic: Aims, tools and techniques of the Icelandic sorcerers. Avalonia Books: London

Davies, Owen. 2009. Grimoires: A History of Magic Books. Oxford University Press: Oxford & New York

Flowers, Stephen [as Edred Thorsson]. 1986. Runelore: A Handbook of Esoteric Runology. Weiser Books: Boston

Flowers, Stephen. 1989. The Galdrabók: An Icelandic Grimoire. Samuel Weiser: York Beach

Karlsson, Thomas. 2009. Götisk kabbala och runisk alkemi. Stockholms universitet, Religionhistoriska avdelingen: Stockholm

Macleod, Mindy & Bernard Mees. 2006. Runic Amulets and Magic Objects. Boydell Press: Woodbridge

Mathias Viðar Sæmundsson. 1996. Galdur á brennuöld. Storð: Reykjavík

![“Þetta er ægirs hiálm n stóre [...] Þetta er Móises innsigle” JS 375 8vo, 46v](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a72d2a74c326d63a3136d7e/1542228419417-YBWQQWWOAF25YCB7QRDR/aegisstore.png)