The Fourth Spell: A Hymn to the God of Secrets

/The fourth spell i know:

If men bind my limbs,

I chant so I may walk.

Fetters spring off my ankles,

and chains off my wrists.– Hávamál st. 148

The grit of life. Our foreheads strain, our fingers bleed, and kneecaps burst with obstacles and hindrances. But ask not for the source of this adversity. Since time began it’s all been fuss and misery. How often are you complicit in the bondage that ties you down. Standing idly by, writhing in the lashes of your own slave morality, fearing the reprisals of an unseen captor.

Listen! He is gone.

Why have not your fetters sprung, now that the door is wide open?

The coast is clear.

Leg it! Run!

And let every taste of blood in your mouth be a communion. And may every tear and drool roping from your lips be poured libations of the sweetest wine. Every gasp of air, fresh or stale, let it be an ode. From self to oneself.

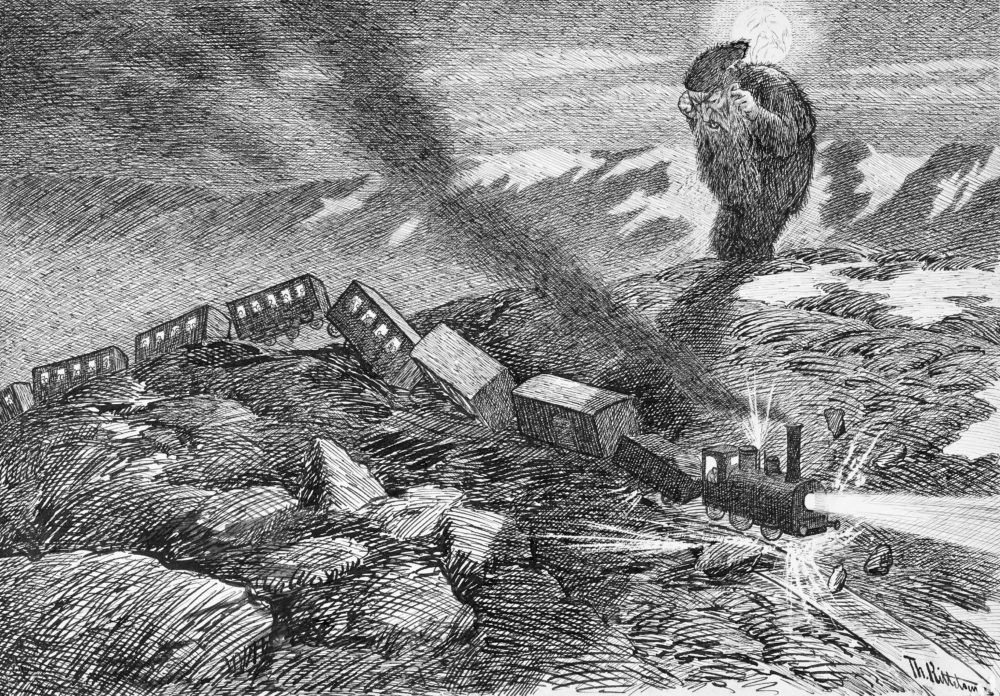

Meditate upon Gagnráðr, lord of tricks and no excuses. Blindr, oh Blind One! Tvíblindi, the Twice Blind! Báleygr, fire-eyed cæsar! Once a serpent, soon an eagle, and often a man where least expected. Master of the blindest bats and sonars. Lord of uncounted secret names, flaneur of the heavens! Cheers to you Æsirian barman, king of the bums! Lord of hosts and feasts, and unwanted guests. Slithering as snake within the mountain, and as a man inside Gunnlǫð, full of deceit. And his lips did slither thrice over the rim of the richest Mead of Poetry, that wellspring of arts, stirrer of minds! Swiftly, then as an eagle across the ranges and canyons. Swift, while the giant Suttung lay chase, eager to repay an ill bargain.

I give that you may give:

A lie for a lie,

promise for promise.

To the fool a king, and to kings a fool, Odin stalks lands far and wide! The Óðr, whose name is craze, wit, and poem. Negotiator of opposites, who knows every border like the back of his hand, and every stepping stone across the steam, and every secret passage, and every buried treasure, and every untold confession a human heart can hide. Pour one out for Odin, that chief transgressor who shamelessly moves across and conquers. To every secret lock there is a key, and to every key he holds a copy. For every hushed wisper is a secret told to him in confidence.

Among his animals are those that stalk. There are those that crawl below, and those that soar. Those that are blessed with grace, and those who delight and flourish in hunting. And just as much he is the master of bottom feeders, those who take to carrion and feast on the dead, his name is uttered through the lips human life itself. Fear and awe, and reserved contempt. Odin, ferret of the chicken coop, and the lord that hunts the ferret.

Most mistrusted wolverine god, small and narrow. Scarecrow, flexible and pliable, stepping seamlessly and elegant between rooms like a ghost. Olgr! Fizzing One! Master of leaders and idiots, and captives and captors. Patron of slayers and the slain, who swims with delight in Campbell's sea of madness, whose bottom is the drowned psychotic. Who knows those that do not know him. Who compels drowning to swim, and the sinking to float, the living to die and the dying to live.

The fetters have sprung.

The only way out, is the way out.

But of course it hurts when buds are breaking.

…

Art by Stig Kristiansen @makroverset

Support Brute Norse on Patreon.com

Related:

The Trollish Theory of Art