These are sad days for Scandinavian museum objects. Last week, 1some 400 objects were viciously burgled from the University Museum in Bergen, in all likelihood bound for the black market. Now, words of lament are howling from across the Swedish border as archaeologists have been forced to destroy artifacts recovered from digs, and objects such as scales, coins, knives, decorated foils, pre-Christian cult objects etc. are sent for scrap metal right on the site, if they are not considered unique enough to warrant conservation. Apparently too precious to own, but not to precious to be thrown.

This has already been discussed elsewhere on English language sites that are, diplomatically speaking, more tendentious in disposition, and where it plays right into the hands of a narrative where Sweden is on a masochistic binge to erase its own cultural memory to better accommodate swarthy hordes from across the sandy dunes. This will not be yet another article about that, but you cannot help but think that with this legislated destruction of their own cultural heritage, Sweden is not doing a very good job at combating the stereotypes pinned against them.

Let's add some much needed nuance: To my understanding, the destruction is for the most part carried out by private companies sourced to conduct routine and emergency digs on behalf of state archaeologists. Additionally, the items bound for the grinder are usually of negotiable historical value. These are digs that are often done in association with construction work, which none the less make up the bulk of Scandinavian digs, to the point where contemporary Nordic archaeology is more or less synonymous with highway projects and the like. Sweden, however, is unique in its employment of private archaeological companies for such tasks.

The fun thing about archaeology is that you never know what you're going to get. Sometimes you get little, sometimes you get a lot. This rings particularly true when it comes to emergency digs, in which the lack of time necessitates many tough choices. I'm sure more than a few artifacts and their contexts have met an untimely demise at the hands of such gambles, but it's debatable whether or not this is problematic if they would have been obliterated by machinery anyway.

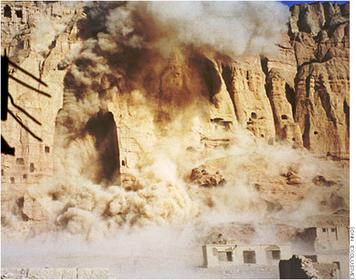

Blasting the past

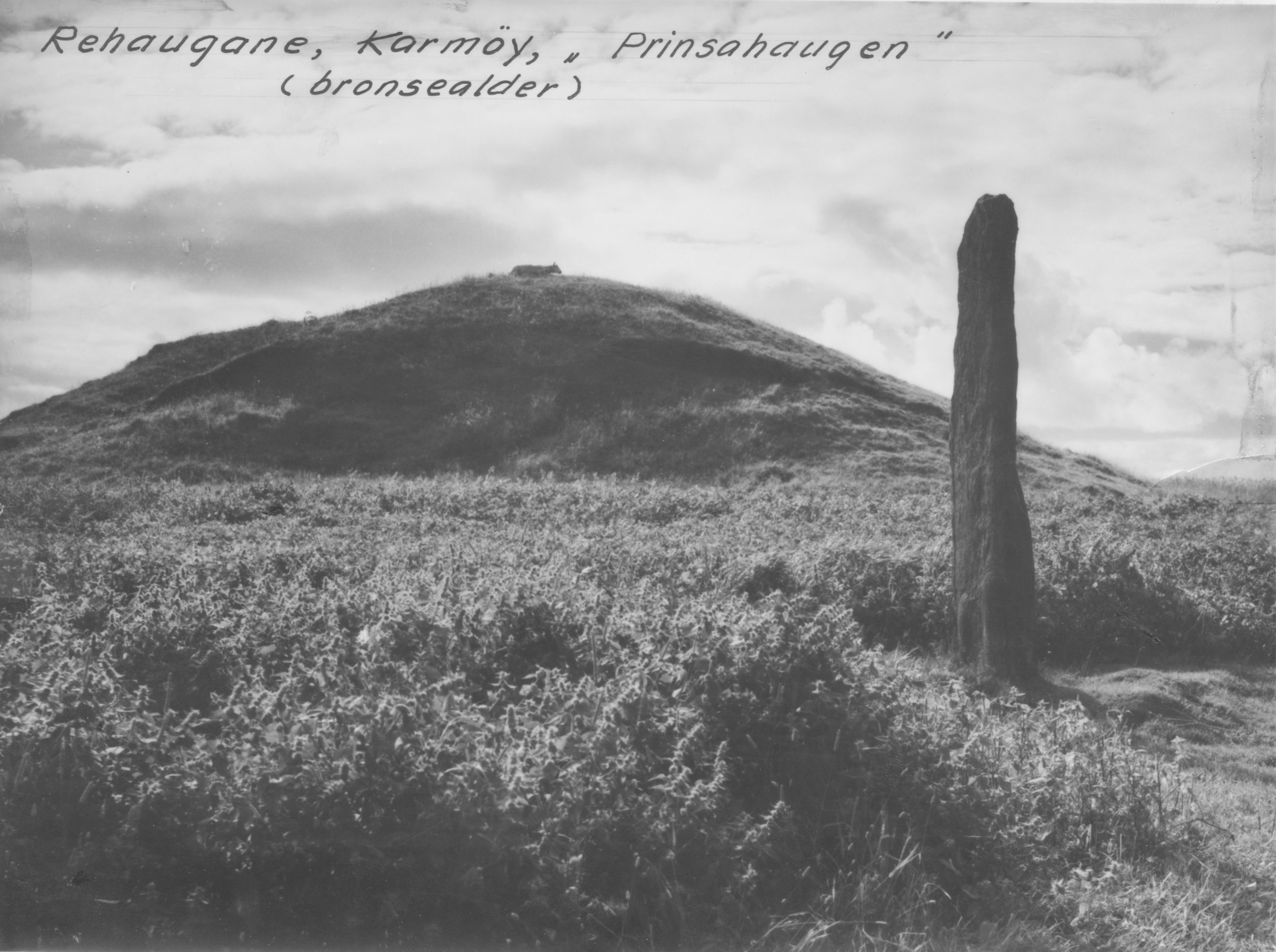

It's not unheard of to find examples of house remains, burials, or even cult sites where archaeologists can do little but step back and let the bulldozers in. In my hometown, there is the particularly grim example of the destruction of the Bronze Age burial mound at Tjernagel. A site unique not only for its impressive size, but for the fact that it's referenced in a skaldic poem from the beginning of the 11th century. The 3000 year old mound was destroyed in 1983 to make room for a since decommissioned radio transmitter. As baffling as this might seem, such practices have generally been accepted sacrifices on the altar of societal infrastructure.

However, extending this logic to artifacts is a new turn, or should I rather say; shockingly old. Especially considering that contemporary archaeology explicitly distances itself from its antiquarian roots in the 19th century, where conservation was entirely up to the excavators who could more or less scrap whatever they saw fit. Deliberate destruction was not entirely unheard of, either, as the fate of the 8th century Storhaug ship shows. Buried in a massive mound on a particularly fertile stretch of farmland on my own native island of Karmøy, it was Excavated in 1886 by Anders Lorange. The Storhaug ship is estimated to have been at least 27 meters long. Three meters longer, and a century older, than the Gokstad ship. Lorange had no idea what to do with such a find, so he rounded up the artifacts and let the local peasants tear the ship apart for firewood.

A child of his time, for sure. I have not met a sane archaeologist that didn't roll their eyes at Lorange's choice of action, so it's shocking to me that any Scandinavian archaeologist would return to the antiquated practice of scrapping artifacts they don't consider beautiful or important enough to save. You know, I really don't want to be one of those argument-by-current-year sort of people, I really do. But that sort of practice would hardly be tolerated in 1917 archaeology, let alone 2017.

The reasoning behind the choice to destroy these artifacts lies with the fact that museum stores are filled with metal objects of negotiable public interest. Okay, they better be filled to the brink, to the edge of absolute collapse, because the case applies to all the other Nordic countries, or Western Europe for that matter, but so far I've yet to see anybody else making screws and bottle openers out of Viking Age iron. The world may be headed off the deep end, we don't need to enforce such dystopian levels of recycling just yet.

It's been pointed out that most of the recycled material is more recent, modern trash that archaeologists are under no obligation to conserve. But there is an obvious paradox in the fact that, in theory, pocketing a rusty nail is a criminal offense but throwing it in the trash is not.

Absurdly, Sweden is the only Scandinavian country that allows private archaeological companies to perform such excavations, but it's significantly harder to acquire a private permit to use metal detectors there than it is in Norway or Denmark. Sweden banned unlicensed use of metal detectors in 1991 (Swedish archaeologist Martin Rundkvist gives an outline of their legality on his blog). Consequently, Sweden reports the fewest number finds from private detectorists, while the opposite is true for Denmark, which appears to be winning the karmic game as far as conservation goes. Whether or not metal detectors should be subject to draconian restriction is debatable, and is only relevant to this discussion as far as it relates to the black market. It's possible to argue that Sweden's restrictive legislation in itself serves as an enabler to so-called nighthawks. That is antiquarian slang for illicit detectorists.