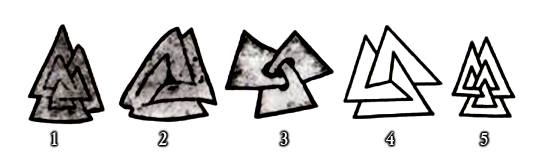

Hey kid, wanna hear about magic in Viking and medieval Scandinavia? This is the first article in what will eventually be a whole series on magic and metaphysics in the Viking and Norse world. In it, I'll offer explanations and explorations on key subjects and terms, such as galdr (chants and incantations), seiðr (let's just call it “textile-magic” for now) and gandr (spirit emissaries). There will be magical projectiles, incantations, sigils and symbols, voodoo doll-like effigies and fetishes, divination, supernatural sodomy, and the massive can of worms that is runic magic. Dear lord, I will most definitely step on a few toes, but hopefully I will give more than I take away.

The viking and medieval world was full of magic, for protection, harm, to predict future events and communicate with forces and spirits. Naturally, all was integrated into how they made sense of the world around them, which was full of unseen entities. A lot of the terms we'll get into have some level of overlap, and grants us a glimpse of the taboos, beliefs and symbols that shaped their day to day experiences.

I presently aim to cover the most important bits of Viking and medieval magic over a span of several months, but I won't shy away from covering the zany world of contemporary spirituality and new religious movements either. Will there be Nazi occultism? Minoan runic sex cults?? Ancient aliens??? Who knows! It all depends on how far down the rabbit hole I decide to go.

The magic of magic

Now, magic is an extremely fascinating subject, but it is sadly misrepresented (and -understood) in public discourse. This warrants an introductory rant to kick us off, which will also serve to clarify my academic and philosophical stances and biases on the subject.

Firstly, I do not consider the notion of magic to be primitive in itself, but rather a feature of human psychology that may manifest itself in various forms of belief and behavior. The Vikings like any other pre-modern society, was not populated solely by superstitious twits who naively wasted their time and resources on self-deceptive practices that never actually worked. They wholeheartedly did believe in its existence, and they certainly felt that it granted them some benefit. Yet, perhaps not in the way people tend to think. Conversely, absence of witch trials is by no means evidence of a lack of magical thought in modern Western society. There's no need to turn to the occult: As an anthropologist might tell you, you'll find endless examples of pseudo-magical thoughts and practices by throwing a brief glance at the world of business and advertisement.

Fantastic and vivid descriptions of magical wonders, as well as their strange and wacky physical effects, are as old as the hills, and I'm sure that snake oil salesmen and quacks of all sizes have always thrived withi.n our ranks. This doesn't take away from the fact that magic has always encompassed a wide range of functions, ideas, and practices beyond whatever hocus pocus our minds might usually consider magic in a strictest sense. A magician may offer counseling and meditation therapy, strengthen social bonds, give pep-talks, and so on. Besides this, there may be many other culture-specific functions of magic that are difficult to pin down and properly discern. Even in the twilight realm of magic and medicine we find, at the very least, the time-tested and scientifically proven placebo effect.

If we are to talk about naive magical notions, then basing one's entire perception of magic on, say, Lord of the Rings says more about the modern reader, than it tells us about the witch doctor.

Believers in magic: village idiots of popular histor

Magic is commonly used as a cheap trick to demonstrate a supposed lack of sense and logical thought, particularly in past societies. Contemporary cultures with strong magical traditions, especially the non-industrialized, are thought of as intellectually or philosophically deficient. There's no room for such nonsense, or so we're told, in the world of scientific materialism and Cartesian rationalism.

Subjectively, I simply don't think this true. Rather, it shows the arrogance of Whig history at its very basest. That is to say: The idea that history is something akin to a bumpy train ride, ever rolling towards inevitable moral truths and intellectual progress. Every year is de facto better than the last, as we await a coming state of societal perfection. I'm no historian of ideas, but people guilty of such thoughts do tend to pity those poor souls unfortunate enough to be born in the horrid, dark chapter of human history colloquially known as the past.

Such an attitude neither helps us understand how past man thought, nor does it bring us any closer to understanding ourselves (except, perhaps, for shedding light on intellectual snobbery). I am not about to unleash a crackpot narrative of a past paradise, but I will scoff and pass judgment on those who squarely pass water in the faces of the giants whose shoulders they stand on.

In my unrewarding struggle to defend past man against slander, the supposed mental simplicity of medieval and ancient people is probably what I hear the most, whether we are debating art, ethics, or religion. Mind you, this does not correlate with low education: There are many academically trained, talented individuals who treat anybody born before the 18th century as downright dumbasses. So it's not characteristic of lacking intelligence or education, by any means – but I do believe it is a distinguishing mark of someone lacking historical literacy, and perhaps a basic grasp of human psychology.

I hope I'm not too crass. It's obviously no crime to disagree with (or not care about) the beliefs of people who died ten centuries ago. But it is important to realize, despite any chronologically imbued misanthropy that, anatomically, their brains were no different than ours. It's unlikely that a random person born in the 10th century was any dumber than you, unless you are some kind of genius. Either way, the psychology of magic is probably as old as mankind itself. Irrational as it may seem, there are probably rationally justifiable, Darwinian reasons for its presence in the human brain. It won't ever disappear, but if it should I highly doubt its loss would be an enhancement to human life.

The academic study of the history of magic, it should be noted, is a fairly young and marginal discipline. Traditionally, Old Norse scholarship seemed more interested in how and when to distinguish magic from religion. When reading older works in particular, they often have an ethnographic tinge, and scholars seldom demonstrate any particular interest or competency in the history of magic proper. Luckily, a lot of great research has been published in recent years, which we shall dive into in future parts of this series!