The Norse saga of Gautama Buddha

/Some time around the year 1250 AD, the Norwegian king Hákon Hákonsson laid eyes on one of his court scribes' latest work: It was a brand new saga – or more accurately: an Old Norse retelling of a Latin story, handed down from Greek sources, describing events that happened in the distant land of India a long time ago. They named it Barlaams saga ok Jósafats.

The saga of Barlaam and Jósafat

The story begins with a conservative Indian king who fears that a hip, new spiritual trend will overthrow his authority. His paranoia grows even greater once he hears word of a prophecy foreshadowing the religious conversion of his one and only son. Hoping to secure his legacy, the king puts the young prince in a secluded fortress, hoping he will grow up totally ignorant of outside life. Meanwhile, the king does all he can to pursue hermits, holy men and other spiritual freaks in a futile attempt to drive them out of his realm. One day a hermit named Barlaam approaches the adolescent prince, whose name is Jósafat, and opens his eyes to the compassionate, anti-materialist teachings of Christianity. The prince is baptized in secret, and Barlaam returns to the desert from whence he came. The now infuriated king desperately tries to revert his heir back to the religion of their ancestors, but to no avail. Western spirituality is there to stay. Instead, Jósafat converts the king, accepting Christ on his deathbed. Finally inheriting the kingdom, Jósafat abdicates. He leaves not only his crown but his entire country behind. Preferring the simple life of an ascetic to the luxuries of a king. He wanders the desert to live with his old master Barlaam.

St. Buddha

If the story sounds familiar, it's probably because you've heard parts of it many times before, as the Buddhist story about the life of Siddhārtha Gautama, whom most Westerners know simply as «The Buddha». To its Norse audience, the Saga of Barlaam and Jósafat served as a moral commentary on the vanity of material life, with the protagonist turning his back on his earthly kingdom to partake in the Kingdom of Heaven. Actually, the name Jósafat is a severe bastardization of bodhisattva – a title denoting a person who has experienced the enlightenment of Buddhahood, but has sworn to stay behind in the world in order to work for the salvation of all living things.

Nobody knows what medieval Norwegians might have thought about the saga's Buddhist roots. Their only knowledge of India came from fantastic medieval romances, where it was described as a magical place inhabited by monsters and elves. As for Buddhism, they were blissfully unaware of its existence. However, far Eastern Christianity was a staple of medieval folklore: From the Nestorian church in Asia to the legends of Prester John. It was a widely believed that the apostle Thomas had brought Christianity to India after Christ's death, which gave credence to the idea that isolated pockets of early Christians persisting throughout the uncharted East.

The Helgö Buddha. Photo: Historiska Museet

From Bengal to Björgvin

Before becoming available to Norwegian audiences in the 13th century, the story had already undertaken an impressive journey: It was brought into Catholic circulation via Greece, who got it through Georgia where it was first adapted to Christianity from an Arabic version in the 10th century. This version had in turn come from Persia. The legend provides an amazing example of how stories can acquire new meanings outside their original contexts as they move across cultures.

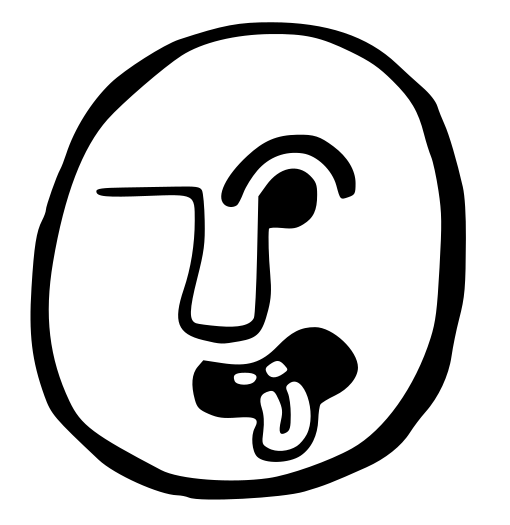

The story is not the first Buddhist creation to reach Scandinavia though. In 1956 a small bronze statuette of the Buddha was found in a viking era settlement on the isle of Helgö in Sweden. Produced in North-East India, the figurine depicts him peacefully meditating on a lotus blossom. How did it get there? As far as the vikings are purported to have traveled, it's very unlikely they had any significant contact with Buddhists, if at all. The explanation is probably more mundane, but interesting none the less: Typologically the statue is dated to the 6th century AD, a time when Scandinavians by all accounts lacked sailing technology. Their rowing capabilities allowed them to trade across the North and Baltic seas, but direct contact with the middle east is pretty much out of the question. Of course, I cannot leave this without addressing the unfortunately named «Buddha bucket» of the Oseberg burial, as well as similar examples from various viking era burials. Don't let anybody fool you: they are Irish, not Indian in origin. The Helgö Buddha is a genuine example though, but it was likely a centuries old antique by the time it reached Sweden, having made its way North on a slow journey that took it generations to complete. Which is pretty impressive in itself. I wonder what they must have thought of it!

Despite any similarities with oriental art, the so-called buddha bucket of Oseberg is Irish in origin.